Who Does The Work?

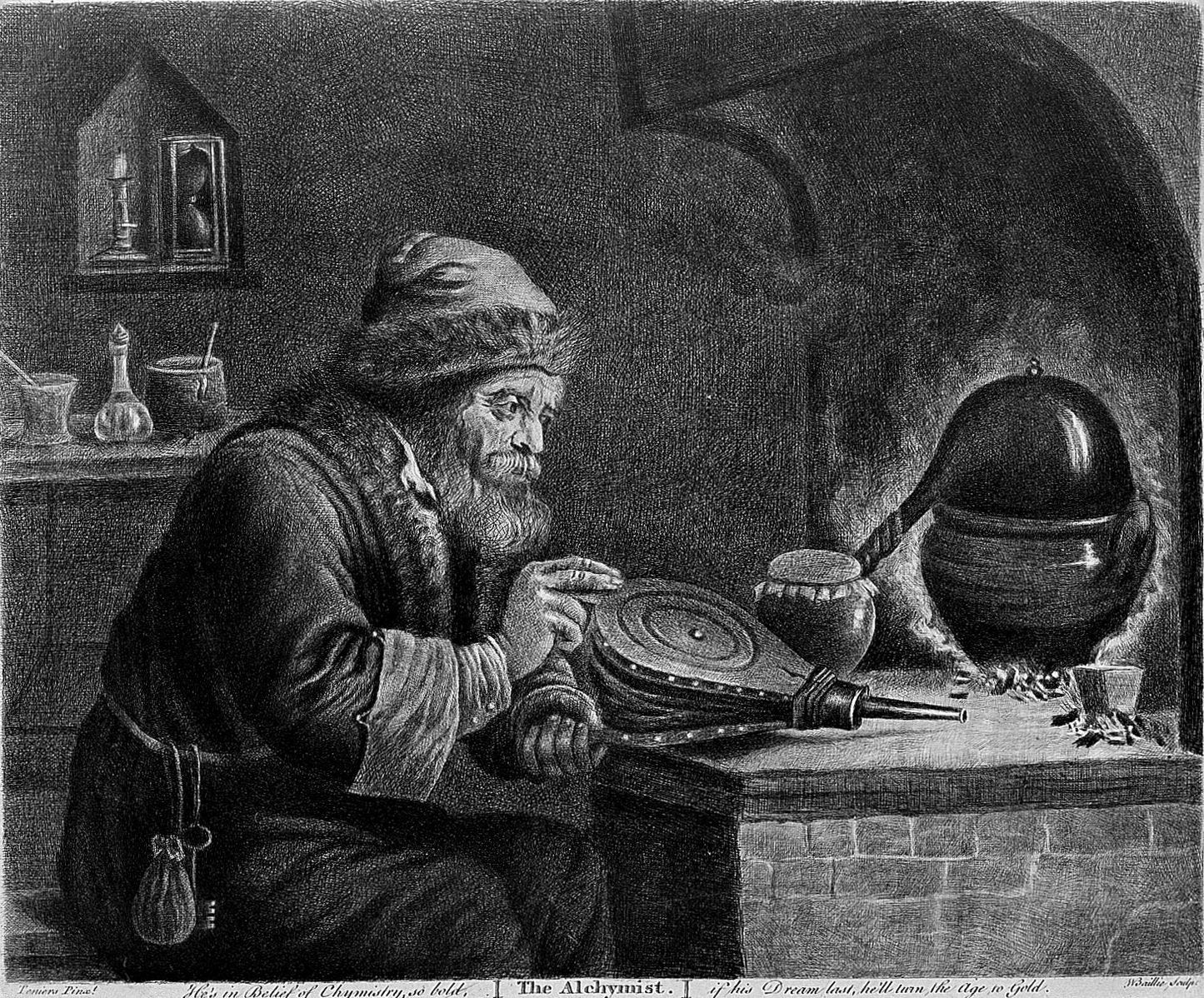

Cultivating an Alchemical Attitude

“It’s not what you do, it’s who does the work which determines what eventuates.” ~ Marie-Louise von Franz1

Last week on the podcast I released the first episode of a planned four-part series on alchemy. In that episode — Alchemy: Mirror of the Soul — I gave an overview of some of the difficulties inherent in the study of alchemy and tried to offer an understanding of how one might begin to find relevance in this arcane subject for one’s own engagement with the inner life. I want to follow up on that introductory discussion here with a look at what could be called the alchemical attitude, that is, the quality of consciousness that was considered necessary for practitioners of the “sacred Art.”

In the episode I suggested that alchemy is an excellent model for what I regularly talk about on the podcast as the practice of the symbolic life. Just before launching into the main theme of this post, I think it would be a good idea to briefly revisit what I mean by the use of that phrase.2 In the inaugural episode of this podcast — Season 1, Episode 1: What is the Symbolic Life? — I put forward the following definition:

“The symbolic life is a recognition that there is a larger life of some kind that we are subject to and which has the character of meaning. It is an affirmation of the meaningfulness of life and a means, a way of living, that enables us to come into contact with that life of meaning. This larger life is that which is attested to by the great works of religion and mysticism, of poetry and music and art, and so much more.”

To this I would simply add that the symbolic life can take many different forms including such things as a religious or spiritual practice, a creative or artistic work, or the conscious attention to one’s psychological growth — what Jungian psychology calls the process of individuation. Each of these paths mediates the (ultimately inexpressible) life of meaning through its particular cluster of images and symbols.

In addition to this, each of these paths requires the cultivation, among other things, of a definite frame of mind, an attitude conducive to the unique rigors of the work — a kind of consecration of one’s being to a larger purpose. This requirement is frequently addressed in the alchemical literature. For example, in a text called the Turba Philosophorum it is stated:

“O all ye seekers after this Art, ye can reach no useful result without a patient, laborious, and solicitous soul, persevering courage, and continuous regimen.”

This statement is worth unpacking because it not only describes the disposition that was considered necessary for the opus, but it can also give us a glimpse of how the alchemists understood the nature of what they were doing. In short, it reveals the religious character of their work. What is being described in this statement is an attitude of reverence.

In his book, Anatomy of the Psyche, Edward Edinger comments on the attributes listed in this passage from the Turba Philosophorum and states that they are “requirements of ego function.” This is true as far as it goes, but I think that it misses the fact that what is being described is something like a devotional practice. These are personal qualities that must be cultivated, not just performed. In fact, they cannot be adequately performed until, in a sense, a person becomes them. As Marie-Louise von Franz states, “It’s not what you do, it’s who does the work which determines what eventuates.”

Patience, according to the text, is the first requirement. However, it is a particular kind of patience — the possession of “a patient, laborious, and solicitous soul.” ‘Laborious,’ as it is used here, should be understood as meaning industrious or meticulous, and ‘solicitous’ has to do with care, concern, and attentiveness. Patience, then, in this context, is probably best understood as that quality that stands in contrast to the agentic, to that which acts, which takes the initiative.

To be patient, then, is to make room for the creative element — something beyond the activity of the ego — to act. Obviously, this is not the kind of model of efficiency and productivity we are used to in the modern world. It is not a means of getting the most done in the least amount of time. It is, in fact, a discipline of waiting, of what I call deep listening.

The next factor is “persevering courage.” This is an interesting element to include in this list. Why would courage be needed? It suggests that something is asked of the individual in this work that pushes them to some limit within themselves. This brings to mind a quote of Jung’s that I discussed in Episode 4 of this season, Imagining Our Proper Life-Task, in which he states “Our proper life-task must necessarily appear impossible to us, for only then can we be certain that all our latent powers will be brought into play.”3

In the alchemical work, the individual was not exempt from the process. It was not simply a set of experiments and operations performed on some external material. The alchemist participated in the work of transformation with their own being. As anyone who has been through the trials and difficulties of analysis knows, real change is hard. Something in us is always pulling back from that fire. To find within ourselves “persevering courage,” then, is essential.

Finally, we are told that the opus requires a “continuous regimen.” This is the element of practice, of discipline. There can be nothing random or arbitrary about this process. One cannot wait only for moments of inspiration or until one feels in the mood to work. Every musician knows that daily practice is crucial, not only to keep one’s skills honed, but also to continue to grow artistically. This same principle holds true for the practice of the symbolic life. If we work at anything consistently our experience of it and our relationship with it is deepened. But we must work. As the poet Rilke puts it, “Being carried along is not enough.”4

It is only when these conditions are fulfilled, we read in the Turba Philosophorum, that a true understanding of the work is possible. As it says in the text:

“He, therefore, who is willing to persevere in this disposition, and would enjoy the result, may enter upon it, but he who desires to learn over speedily, must not have recourse to our books, for they impose great labour before they are read in their higher sense, once, twice, or thrice.”

The essence of this passage is that whatever meaning is to be disclosed through the work is contingent upon the kind of consciousness that performs it. Here the attributes of patience, courage, and discipline are contrasted with the attempt to “learn over speedily.” In other words, there is no shortcut. It is not simply a matter of learning a set of formulas, techniques, or recipes. And it is not about gathering and retaining information.

Everything must be understood, the text states, in its “higher sense.” This points to the need to internalize and metabolize what has been discovered. It is not just knowledge that is sought, but wisdom, and this is gained only when our experiences penetrate to the depths and change us. It is not what we do, it is what we become that matters.

As the religious philosopher Raimon Panikkar writes, “Only what has penetrated me and then springs out of me in a spontaneous fashion, has life, power, and authority.”5 And with this, Jung concurs. In words that exactly echo those of Panikkar, he writes:

“The most beautiful truth — as history has shown a thousand times over — is of no use at all unless it has become the innermost experience and possession of the individual. Every unequivocal, so-called 'clear' answer always remains stuck in the head and seldom penetrates to the heart.”6

Until next time.

Alchemical Active Imagination by Marie-Louise von Franz

For a more complete exploration of the symbolic life, see my book, Religious but Not Religious: Living a Symbolic Life.

C.G. Jung Letters, vol. 1

“Just as the Winged Energy of Delight” from Selected Poems of Rainer Maria Rilke (Translated by Robert Bly)

A Dwelling Place For Wisdom by Raimon Panikkar

Collected Works of C.G. Jung, vol. 18, par. 1292

It is not easy being a human being.